Human nature’s appetite for fun and knowledge far exceeds measurement. Fun and knowledge are notions that brook no scale. There is no unit of measurement for either fun or knowledge. The old saw still works, true as ever: Not everything that counts can be counted and not everything counted counts. Fun and knowledge are hardly unique in this way. Truth, goodness and beauty can’t be measured on any meaningful yardstick. Deliciousness has no spectrum. Nothing is objectively yummy. Who’s to decide? The Cordon Bleu chef, the short order cook, the cannibal? What’s the prettiest sound? The Vienna Boys Choir? The [Dixie] Chicks? A kitten purring, a baby cooing, a ’61 Aston Martin DB4 GT Zagato roaring into Monaco? What is knowledge? How to transplant a heart? How to spilt an atom, bake a soufflé, tune a Stradivarius —string a Stratocaster?

Fun and knowledge come at us day and night in myriad ways. But the idea on offer here concerns only the narrow area of marketing fun and knowledge. Transactional Man has always tempted and proffered and profited from the marketing of fun and knowledge. From the sly and able serpent with his Tree of Knowledge apples to the fire-bringers at the neighborhood Apple Store, the market for fun and knowledge is as old as humanity and every bit as exciting.

So, what’s the idea?

The idea is this: Books and recorded music are pure fun and knowledge. The artists and companies that create these fun and knowledge goods are among the most ingenious and intrepid among us.

But…

The artists and companies that market these fun and knowledge goods could, with but a slight shift in perspective—just a little nudge-—foment a renaissance in books and recorded music marketing.

The idea that retail book shelf space available to marketers is not only limited—but shrinking!—is a flat-Earth-Beyond-Here-Be-Dragons view of the marketplace whose time has come.

What if physical real-world places and people perfectly perfect for marketing books and recorded music were limitless…?!

* * *

Linear thought—from papyrus to eBooks—is what got us out of the caves, across the oceans and onto the surface of Mars. The intergenerational transfer of fun and knowledge was slow-going for our first couple of hundred thousand years. All the best guesses peg writing’s birth at a scant 5,200 years ago. It took well over two millennia to get from the Sumerian scratchings to that first starter set—the J writer’s Pentateuch; a couple more centuries gives us Homer; another couple of millennia brings Shakespeare. A quick four or so centuries from there brings us to the last Bowker’s Books-In-Print ISBN Output report (2013) wherein we learn that 304,912 new books hit the shelves—about 35 titles per hour all day and all night all year. This hard to see but nonetheless astounding enterprise produces for Posterity in a single year a stack of titles (at an inch each) that would soar up to the heavens as tall as a stacking of the highest two dozen Manhattan skyscrapers plus the Statue of Liberty. This jaw-dropping genius and industry includes:

- One novel every ten minutes

- Close to nine cookbooks a day

- Slightly more than thirty business books a day

- A kiddie book every sixteen minutes

Putting a book together, any book—for the nonce, the narrow or the numinous—takes an act of daring. From the empty-pocketed wretch who has to conquer the blank page to the gambling editor who has to hedge or plunge, there’s no comfy science to it. Publishers of yore, the eponyms of the great and good houses, were impresarios, tastemakers, Promethean renegades. The masters of the game today obey a clockwork of corporate fiduciary duty in thrall to an evangel of Big Data-as-panacea.

Meanwhile…

The Authors Guild (2018) says its members raked in annual mean earnings of $6,080 in “author-related income.” The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics is more sanguine: The Bureau finds 131,200 “writers and authors” shoveling in $67,120 a year. While the government finds authors doing an order of magnitude better than the guild estimates, those banging out the words for that stack of books that could tower up five miles into the sky are rewarded by the marketplace markedly less than dental hygienists ($77,090 in 2020).

Old Dogs and New Tricks…

The AAP (Association of American Publishers) sold $26 billion in 2019—about 70% of the amount that the APPA (American Pet Products Association) sold in pet food. The Frankfurt Fair, publishing’s oldest market, dates back to 1074. Pet food was invented by a lightning rod salesman about a hundred and fifty years ago. How did pet food marketing get the jump?

Pet food marketers are untrammeled by bashfulness—or reason…or tradition or data of any size. They just get out there and plunk the goods where the people go.

Dogs have been domesticated for 40,000 years, cats for 4,000. They ate table scraps until just a minute ago. Now, thanks to some of the zaniest marketing in the marketplace, there is not only dry and wet pet food, there is refrigerated pet food. There is frozen pet food. There are doggie ice cream trucks cruising dog parks. $36.9 billion in 2019.

Imagine the Potato Chip Boutique and the Soda Pop Pro Shop…

Booklovers and book marketers have 2,500 or so cozy Edens in which to perceive and exchange value. The membership of the American Booksellers Association constitutes a lifeline channel trafficking fun and knowledge in, more or less, the centuries-old ways and means.

And that’s lovely. But 98% of the population are book-neutrals—people who can read perfectly well and whose appetite for fun and knowledge is perfectly healthy, but who will in no way encounter a book on offer in their daily rounds.*

The Pepsi-Frito people take in about two-and-a-half times as much as the combined total of the book publishers. How would PepsiCo’s bounty ever, ever, ever be possible if they relegated themselves to 2,500 lovely little potato chip boutiques and soda pop pro shops instead of a vast network of omnidirectional ever-present ubiquity?

What if the fundamentals of potato chip and soda pop marketing were mastered by book publishers?

* * *

The idea of the idea of the idea is that dissemination has some basic precepts and with but a slight shift in perspective—just a little nudge—a whole new world comes into view—numbers too big to be ignored and too simple to be wrong.

Myths will crumble. Horizons widen. No crazier than Paine’s Common Sense: “We have it within our power to begin the world over again…The birthday of a new world is at hand.”

Common Sense, that first American viral bestseller, despite its suicidally treasonous incitements and manifestly bizarre extravagances of mind, sold to one in five of Paine’s Internet-free, nearly illiterate countrymen.

That’s like merchandising 66,500,000 copies today…

* * *

Let’s call it R-E-A-C-H. Five virgin areas for channelization. Like Columbus gainsaying Isabella & Ferdinand’s court wizards: “Trust me, it’s that-a-way.”

No app, algo or gizmo required: All that’s needed is recourse to a few indefatigable truths about our ever-nebulous human nature. A few years ago, the bestselling Nudge authors barnstormed the world with their brilliant-cum-banal mantra:

“When you want people to do something, make it easy for them to do it.”

This “insight,” however, ain’t new. The serpent in the garden used it to merchandize apples. The Phoenicians mastered the idea with such finesse that they had to invent the alphabet just to tally the loot. Then, of course, there’s our own polestar merchandizer of the Modern era:

In the deeps of the Great Depression, a 24-year-old college drop-out and failed tractor salesman named Herman Lay sent out 200 letters seeking a job. He got one reply. He got the job but turned it down. He couldn’t see himself wearing out his remaining shoe leather and tire rubber on the dusty back roads around Nashville selling potato chips. A week later he changed his mind; a year later he broke records and added a salesman; 23 years later he had 1,000 workers and went public.

By age 11, little Herman’s gut was telling him how to sell: sit your wagon across from the ballpark to sell Pepsi Cola! By 55, he merged his potato chip empire with Pepsi Cola and sat himself Chairman.

Lay’s progeny, those beloved purveyors of colorful packages of fat, salt, grease, sugared water and concomitant nonsense, netted $7 billion on $67 billion gross in 2019.

Herman Lay’s channelizing worked brilliantly because he overlooked reality:

1) Potato chips were, by his first day on the job, an 80-year-old idea that already had reached, supposedly, everywhere possible.

2) No one actually needed them in the first place. Thanks to his peculiar blindness, today’s potato chip marketers enjoy both ubiquity and marketing’s nirvana: no fixed price-point perception. He had no new tools, no new product…

He simply reached where most of the people went most of the time and made it easy for them to reach for his goods when they got there. He built an entire empire from the backseat of his Model-A Business Coupe armed with but a Phoenician’s culture-bearing irreducible essentials: Get the goods into the eyeful, under the nose, at the fingertips:

School cafeterias, hospital cafeterias, prison commissaries, the cocktail bar in the lobby at the ballet, the snack bar at the bowling alley, behind the bar at the five-star luxury hotel’s mahogany-paneled grille room, next to the mustard at the sidewalk hot dog cart…

Retailing = Contrived Serendipity

A market is a point in space and time where value can be perceived and exchanged.

Nothing more, nothing less.

The marketplace begins at the end of the marketer’s nose and extends to the edge of the imagination.

Book publishers and record labels sell only a fraction of what they could because they merchandise books and music in only a fraction of the places where books and music could sell.

Books and music everywhere: in every eyeful, under noses, at fingertips.

Books and music can complement, finesse and sharpen any and every retail offering.

Books and music can add risk-free continuous profit to any and every retailer’s net-net.

Books and music on offer everywhere threaten bookstores no more than restaurants threaten grocers.

If it’s not there, it’s not there.

If it is there, it cannot not be considered.

If it isn’t where they’re looking, it isn’t what they’re buying.

Interrupt Incite Excite Satisfy

The early popes didn’t fill their churches by making the seats plusher but by increasing the appetite for salvation in the society. The throngs of pagans, heathens and savages must want to join the flock. The whole enterprise became a verb: Christianize.

That is the essence of the nub of the nucleus of the thing of the thing:

Channelize.

What if the booklovers were joined, every now and then, here, there and everywhere by the book-neutrals—the worldwide mass of literate-enough fun-seekers who simply never think to write “go to bookstore” onto their To Do List? Presently, there is almost no chance that book-neutrals (98% of the population) will serendipitously stumble upon a tantalizing book or piece of recorded music in their daily travels…

Book-neutrals, that vast majority who never consciously go looking for a book, work, eat, sleep, play and course about in an embarrassingly bountiful marketplace nearly devoid of books-on-display.

If books and music were in every retail eyeful, under noses and at fingertips—no less importuning than the ubiquitous potato chip—then books and recorded music marketing could master a whole new universe.

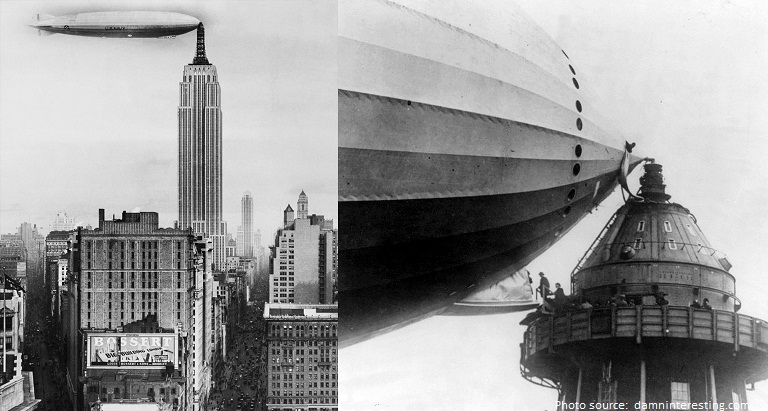

When the venerable tries to squeeze into the newfangled, hilarity and tragedy are always on hand.

The aerodynamics, structural integrity, solvency and sanity on offer here are beyond question.

Is this groupthink? Collective delusion? Feudalism’s last gasp?

Why are the powers-that-be so often so absurd?

The porter on the right is mumbling to himself, “Sure fellas, it ‘works,’ but it’s not much of a way to keep two million souls at a time aloft, is it?”

Einstein protégé Leo Szilard used to say that the two necessary criteria for picking one’s friends are a sense of humor and a sense of proportions.

The next big thing in books and music marketing need not come from a technology company. The next breakthrough in merchandising and channelizing books and music need not come from yet another app or contraption or whizzbang venture capital start-up or direct-to-consumer contrivance or streaming scheme and, most certainly, the next big thing won’t come from Amazon.

Horse traders didn’t invent the horseless carriage, the telegraph company didn’t invent talking across wires, the Sea Lords of the British Admiralty didn’t invent flying across the unpeopled skies, and the telephone company, most certainly, didn’t invent the iPhone.

Why not?

Human nature:

When you’re running the show, upending the show doesn’t occur to you.

Jobs said, “…people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” The iPhone wasn’t simply an innovative new phone. Jobs wasn’t “solving a problem.” He was daydreaming. He asked himself, How much fun and knowledge could we carry in our pockets? He answered himself by taking the telephone, the TV, the radio, the telegraph, the typewriter, the record player, the notebook, the Polaroid, the home movie camera, the bookcase, the library, the bank, the Post Office, the shopping mall, the movie theatre, the peep show, the alarm clock and the cash register and putting them into everyone’s pocket.

That’s what, every now and then, can happen when you upend the unquestioned answers and dream up the unasked questions.

Saint-Exupéry knew the feeling: “A rock pile ceases to be a rock pile the moment a single man contemplates it, bearing within him the image of a cathedral.”

What’s the Jobs-grade question to be dreamt up here? What’s the treasonous revolutionary Thomas Paine-size daydream? What can be done with what’s to hand to change the very nature of what’s to come?

Sure, re-arranging the furniture and re-spicing the shelves and re-sizing the floors come to mind. Ever snappier apps, of course. But…What if…for an hour, maybe for a whole afternoon, we abandon the safe-n-easy answers, look the absurdity right in the eye and ask some mind-bending breathtaking heart-stopping questions?

- What if we could actually crack the code of discoverability?

- What if, by channelizing, we could create, control and curate a nearly limitless supply of real-world retail merchandising sweetspots?

- What if books and music marketing suffers from nothing more than a transitory crisis of perception?

- What if we could forever change the way the marketplace sees eBooks, digital music downloads, vinyl, CDs, audiobooks and trade books of every size, shape and subject?

- What if, by nothing more miraculous than a shift in perspective…just a little nudge…books and recorded music could know a whole new day? What if heretofore undiscovered channels—channels utterly unmolested by convention—came into sight around each corner, under our noses, at our fingertips?

- What if we could harness the simple and ancient fundamental properties of trade to double the size of the marketplace for books and music…for starters?

- What if we could show books and music marketers a new way to look at, to get to and to profit from channels wider, deeper and more articulated than ever dreamt before?

- What if we were to present the marketplace with channels that Google, Apple and Amazon are constitutionally incapable of seeing?

- What if millions upon millions of new prime real-world to-die-for retail merchandising sweetspots are there for the asking…?

The problem we have isn’t like those two impecunious bicycle makers from nowhere trying to persuade the British Admiralty that, soon enough, those who rule the skies will rule the world. It’s more like trying to explain to Orville and Wilbur themselves that their kids will live to see humanity fly not just across the dunes and plains and seas but all the way to the moon. A shift in perspective—just a little nudge—doesn’t cost any cash, but bending the mind comes at a price:

One sounds like a nut doing so.

With just a shift in perspective—just a little nudge—we can put books and recorded music on offer everywhere—in every retail eyeful, under noses and at fingertips.

Strangely, the first question isn’t “How?”—but rather, “Why?” Why books everywhere? Because Sagan and Zappa are right. Books and music—fun and knowledge—make people a little happier and a little smarter, book by book, song by song, thought by thought, feeling by feeling.

And if it’s within one’s power to make people a little happier and a little smarter, well…

Why not?

And, happily, there’s a helluva lot of money to be made in it, too.

Once we can agree that a little more fun and knowledge here and there would be nice, the rest is easy.

No Prob!

The first thing we’ll have to do is abandon the tedious rhetoric of “problem-solving.” We are not talking about solving a problem. Publishers, record labels, writers, musicians are all doing fine. There isn’t a “problem.”

There is, however, an astonishingly huge opportunity.

Problem-solving : marketing :: nutrition : candy

It’s nice, but it’s hardly necessary.

What “problem” is solved by an Internet-enabled toaster or a pet rock or three hundred kinds of breakfast cereal in every supermarket in every neighborhood?

In 2019, Rolls Royce sold a car every 102 minutes of the day and night, Porsche sold a car every 2 minutes of the day and night and Rolex sold a watch every 40 seconds of the day and night.

It’s highly unlikely that problem-solving figured in too deeply in any of these 1,085,952 fun-filled transactions.

Books and music marketers know their stuff. They do fine. But…

You show me a couple of booklovers and I’ll show you 98 book-neutrals that love fun and knowledge just as much as any booklover.

And music-streaming-as-savior? Please. What bottled water marketer worries about the ubiquitous free streaming water available to everyone everywhere? The IBWA (bottled water) outsells the RIAA (recorded music) by billions. How? By ignoring reality completely and selling their goods at a price 5,665 times more than their streaming competitors!

“How” isn’t the hard part. Getting marketers to ignore “reality” is the hard part.

Drop us a line.

Peter Cook

*Book-Neutrals vs. Booklovers: Most people don’t refer to themselves as booklovers except under certain pressures and atmospheres–cocktail parties, first dates, at the counter in a bookstore, etc. Booksellers call most of their customers booklovers. Publishers, aided by this or that form of sales receipts, gin up interesting terms like “power buyer” (more than x books per year, month, week). Booklover, much more than fusty locutions like bookworm or bibliophile serves to describe those predisposed to wander into bookstores. Google finds 12+ million hits for “booklover” and 20+ million for “booklovers.” The term, while not precise, is a wholly useful description. Book-neutrals is a word for people who get safely through the year without the aid of a bookseller. It’s most people. People who frequent bookstores can’t believe that everyone doesn’t frequent bookstores–which is nothing more sinister than a little confirmation bias colored, maybe, by some clustering illusion. Not unrelated is the recent Pew Research finding that a quarter of all Americans admit to (brag of?) not having read a book in the past year.

The usefulness of the term “book-neutral” comes in when trying to fathom how one of the most incredible inventions in human history can go unseen by most everyone. “If-it-ain’t-there-it-ain’t-there.” A little Fermi Math always adds an element of accuracy and sciency delight to the art of estimation (see Nobel Laureate and chain reaction pioneer Enrico Fermi on his calculation for how many piano tuners live in Chicago): The AAP’s trade book (bookstores and non-academic channels) sales (2019) was $16.23 billion. Average trade book at wholesale is $8 +/- That makes for a couple billion units. Divide that by the 2,500 ABA bookstores (for argument’s sake) and we get about 2,200 sales/store/day. 2,200 people per day per 2,500 bookstores is 5 1/2 million–or 1.65% of the U.S. population (2021). Round it up to nearest person–that’s 2 booklovers per 98 book-neutrals.

Back-of-the-envelope guesstimation is both necessary and quite often sufficient for great unknowns: Whether the question is how many galaxies in the observable universe or how many jellybeans in a jar or how many of us are not presently in search of book or record album, estimating whatever is observable is the way to go.

The idea of the idea of the idea remains central: Wouldn’t it be a damned good idea to put a little more fun and knowledge into the daily course of everyone’s comings and goings?